Changing climate affects timing of citrus harvests

By Haley Anderson

Scott Suddarth picks a Calamondin lime with clippers to avoid damaging the fruit peel.

Photo by Ashley Hodes

During the first University of Arizona citrus harvest this semester in early February, students and volunteers ditched their coats and enjoyed the sun’s heated rays in their shorts and sleeveless shirts.

In recent years, such as 2013, heavy winter freezes have been troublesome for farmers and citrus crops in Tucson. That was certainly not the case so far this season. Citrus fruited early this year, which some consider another sign of climate change.

“This year, grapefruit was harvested in November. We have never harvested grapefruit before January,” said Barbara Eiswerth as she rolled up her sleeves to pick a Seville orange during the February harvest, organized by UA LEAF – Linking Edible Arizona Forests on the UA Campus. Eiswerth directs the Iskashitaa Refugee Network and works with UA LEAF, a project supported by the UA Green Fund.

Tucson is experiencing an incredibly warm spring, said Paul Brown, a UA Cooperative Extension specialist in biometeorology. Brown founded the Arizona Meteorological Network (AZMET), a network of weather stations in southern and central Arizona that monitor weather data like chill days and evapotranspiration for agricultural and vegetation purposes.

“The soil temperature in Arizona is 4 to 5 degrees Fahrenheit above average,” said Brown in mid-February. “Right now, the citrus season is progressing to be 10 days to two weeks ahead of time.”

Tucson and Phoenix have been experiencing higher temperatures, with 2014 being named the hottest year on record for both cities.

Arizona is not the only place experiencing record temperatures. NOAA declared 2014 the hottest year on record for the entire globe, with 2010 as a close second. The top ten of the hottest years on record have all occurred in the last 17 years. www.ncdc.noaa.gov time.com

Local data from the Tucson region shows that the timing of budding and leafing for certain plant species has been changing in the past few decades, noted Theresa Crimmins, who works on a program called “Nature’s Notebook” that encourages people to document flowering of plants to observe seasonal changes and their relationships with weather and climate. usanpn.org

“Trees use temperature as a trigger to know when to leaf and bud,” Crimmins said. “Environmental conditions change due to climate change, but the climate is not changing consistently.”

Flowers and fruit may exist on the same branch of Calamondin lime trees (Citrofortunella microcarpa).

Photo by Ashley Hodes

Although there has been record-breaking heat, there have also been three heavy freezes in Tucson in recent years: 2007, 2011, and 2013. Glenn Wright, a Cooperative Extension horticulturist for the UA School of Plant Sciences, said he sees these seasons of higher than average temperatures and early citrus fruiting as part of normal climate variability rather than climate change.

It’s challenging to link any single event to climate change that is triggered by human activities, such as burning gas in vehicles and using gas and coal-powered electricity to heat and cool homes.

Overall, temperatures have been warming in the last 20 years, said Brown. In Tucson, even with early warm temperatures, there is always a chance of frost in March, he cautioned.

While high temperatures that exacerbate drought in the Southwest made national news, the Northeast experienced freezing weather for much of the 2014-2015 winter season.

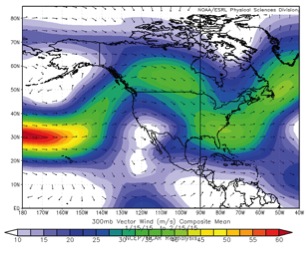

These extreme temperatures on the opposite ends of the country relate to the jet stream, high-powered winds high in the atmosphere that help drive weather. The jet stream held a wavy pattern across the U.S. for months, and this pattern has been recurring seasonally for the past few years. This year, it brought cold Arctic air down to the Midwest, Northeast and even Florida.

The image above shows the path of the jet stream accross the U.S. with the colors indicating wind speeds. The stream is

generally associated with wetter weather, and it can also carry cold air from the arctic further south.

Figure Credit: NOAA/ESRL Physical Sciences Division

The jet stream also can adopt a wavy pattern that brings freezing temperatures down to Tucson, as it did in 2007, 2011, and 2013. This year its dip down from the Arctic occurred further east, as illustrated by the image (Figure 1).

Scientists are still actively researching the behavior of the jet stream and how it might be changing in relation to climate change, noted Michael Crimmins, a UA Cooperative Extension climate specialist.

Researchers propose multiple possibilities for the persistence of the wavy jet stream. Possible culprits include warmer temperatures in the Arctic, warming water in the tropics, and declining Artic sea ice. http://www.climas.arizona.edu/sites/default/files/SWClimateOutlook_FEB2015.pdf

“The connections to overall global warming and these wild jet stream patterns of the last couple of years is not all that clear yet,” Crimmins explained. “This is something I have been puzzling over.”

Overall, the likelihood of freeze events will decrease over time because of the climate change, but it will never go away, Crimmins reminded. Brown agreed.

“One of the projections for the future is more variability and extreme events,” said Brown.

As a result, fruit growers need to keep their eyes on the weather as well as the climate. Watering schedules and watering amounts to plants and vegetation should be adjusted accordingly.

Although the trees at the Slonaker House were ready to be stripped of their bright Seville oranges, the fruit can persist throughout the summer if the trees are well watered, Eiswerth said.

“Out of all the citrus, it stays on the tree the longest,” Eiswerth said. “It is exciting to see if a tree is well taken care of it can last till August when they usually only last till May.”

A volunteer extends his picker to reach the Seville oranges in the Slonaker

courtyard.

Photo by Ashley Hodes